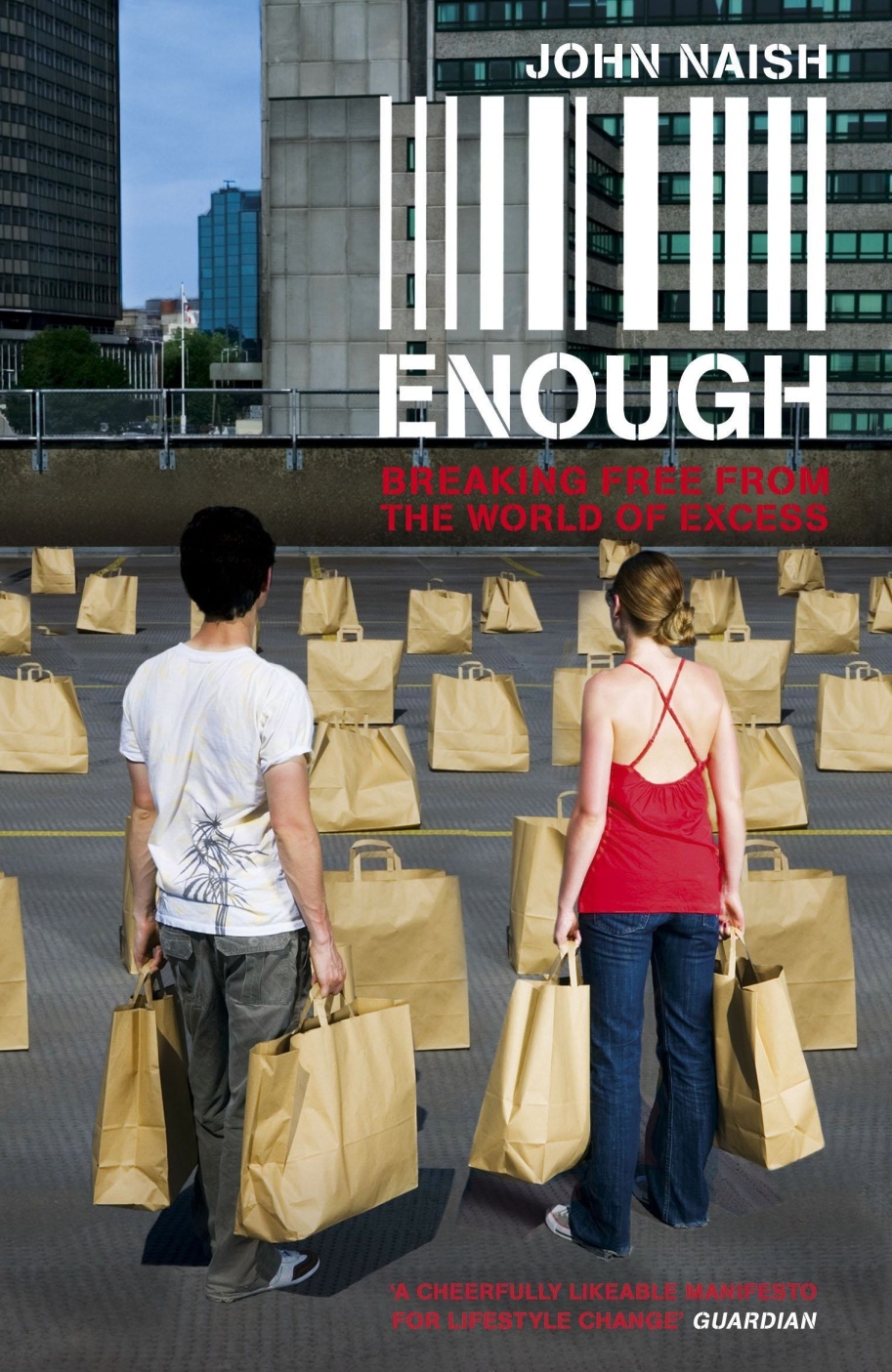

John Naish’s book ‘Enough’ presents what’s described on the front cover by The Guardian newspaper as a “manifesto for lifestyle change”, which Naish calls ‘enoughism’. However, given that he explicitly states that the current “unsustainable” economic system must be changed, ‘enoughism’ is therefore necessarily also a political ideology requiring government action.

Here’s Naish’s argument in a nutshell: the net effect on the health of our minds and bodies and on our spiritual well-being of society’s preoccupation with the acquisition of consumer goods (i.e. ‘consumer culture’) is negative – therefore we should change our lifestyle. Furthermore, should the current economic system remain it will inevitably lead to ecological catastrophe – therefore we must radically change it as soon as possible.

What I found peculiar is that six chapters of this nine chapter book pass before Naish even comes close to discussing economics, which is a bit odd considering his thesis is primarily about changing people’s behaviour as consumers; consumers purchase goods and services and these are economic actions. He starts off by asserting that Keynes “helped to navigate Britain out of the mass unemployment of the 1930s after orthodox economics had failed.” He doesn’t explain what he means by “orthodox economics” but I suspect he broadly means free-market capitalism unregulated by governments because this is the almost universally believed myth surrounding the Great Depression. The story goes that free-markets failed, people stopped buying and started hoarding and so governments had to step in and not only ‘stabilise’ the economy but also ‘stimulate’ it with deficit-spending to prevent social collapse. The story concludes that only the advent of World War II finally dug everyone out of the Great Depression.

This meme subsequently propagated through the vast majority of the minds of several generations of people the world over and shows little sign of dying out. The belief today that government control of the economy – at the very least currency and interest rates but the more the better – is an absolute requirement of prosperous and peaceful societies and that rapid government growth, government monetary expansion and government deficits are beneficial to society is stronger than ever in most countries. Our parents’ parents were raised with this belief, our parents were, and we were. It’s taught in every school and is rationalised in every newspaper. We hold The State over us and this meme provides the strength for our arms.

Explaining the full history of and true primary causes of the Great Depression is beyond the scope of this article, but it suffices to summarise and state that U.S. government monetary management (or rather mismanagement) in the decades preceding the Great Depression, in the form of an unsustainable credit-boom in the 1920s, caused a series of economic booms and busts and ultimately turned a recession into a depression – which became the Great Depression because it impacted economies all over the world. In the UK, a prolonged period of high unemployment was one of the main effects its economy felt and is traceable in part to Winston Churchill’s decision as chancellor of the exchequer to return to gold at the unrealistic pre-war parity and also in part to the high unemployment benefits (relative to wages) available after 1920.

The economic myths surrounding the cause and resolution of the Great Depression have been thoroughly debunked by praxeological economist such as Ludwig von Mises and Murrary N. Rothbard, many decades ago, who understood that the mathematical approach to depicting/predicting economic behaviour is flawed. The economic reasoning Mises, Rothbard et al presented remains superior to this day of that of the glut of mainstream Keynesians, who have happily jumped on the short-term government gravy-train of credit expansion and deficits because they think it’s good for society, and all the while the empirical economic evidence falsifying their beliefs continues to mount.

Further on in chapter seven Naish’s arguments reveal that he miscomprehends the very purpose of economic study in general and also that he holds Keynes responsible for the lifestyle choices many people are making today. Naish says: “Keynes seems to have ignored the possibility that, once we’d got the ‘economic problem’ solved, we would use our new-found liberty to shackle ourselves into chasing ever-more possessions, celebrity, happiness, junk information and all the other ever-mores.” Keynes was just a man, and the fact that he didn’t accurately predict what society would look like seventy years into the future shouldn’t be surprising, nor could we realistically expected him to have. Keynes wrote an economic thesis, which, yes, was flawed, but ultimately it was those individuals in power in the UK and America at the time and over the subsequent decades who gave individuals no choice but to act within the economic environment manifested by it.

He writes that the Keynesian mathematical approach to economics has “produced theories that can help us to predict what happens in world markets (Austrian economists would contend this), but it fails to explain our constant drive for increasingly wasteful possessions.” He’s correct that economics does fail to explain this, but it is not the purpose of economic study to explain why an individual seeks to obtain a certain goal, but merely whether a chosen means Y will achieve a goal of X. The reason why someone wants the new iPad when they have a perfectly serviceable one that is only 2 years old cannot be calculated by any method of economic study, it can only be understood to some degree or other by studying the individual.

Later on in the book it becomes clear that Naish is completely unaware that an alternative to the flawed mathematical approach to economic study does exist and has existed for over a century, commonly known now as the School of Austrian economics, when Naish asks: “Why aren’t we putting any significant brainpower into exploring and evolving alternatives?”

We have done already, and quite some time ago! The great minds of economists such as Adam Smith, Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard, as well as the philosophical genius of free-thinkers such as Ayn Rand have developed and clearly defined the rational alternative to Keynesian economic theory enacted by governments. Tragically, however, government-run lower and higher education and government manipulated mainstream media have had the effect of obscuring their brilliant work almost completely for several generations.

Naish goes on to ponder: “What answers might we get if we paid some of the brightest, most focused economic brains in the world to explore wholly new approaches to develop a viable alternative to constant-growth capitalism? It would be fascinating to find out out…” I strongly suspect that the possible alternative of a complete separation of government and economy has not even entered into his thinking due to the widely held assumption that government control of the economy to some degree or other is necessary. Just before this passage he states that “the financial crisis has shown once again how even the best, most highly paid economic brains in the world are unable to keep our current system of global economics safely on the tracks”, which having just correctly pointed out that it has become painfully evident that no single man or group of men can manage an economy, results in naish contradicting his own argument. He never even considers the possibility that perhaps trying to ‘manage’ and ‘direct’ an economy as if it were a computer network or a machine is simply not possible. Ludwig von Mises summarised this brilliantly:

“The mathematical economists are almost exclusively intent upon the study of what they call economic equilibrium and the static state. Recourse to the imaginary construction of an evenly rotating economy is, as has been pointed out,1 an indispensable mental tool of economic reasoning. But it is a grave mistake to consider this auxiliary tool as anything else than an imaginary construction, and to overlook the fact that it has not only no counterpart in reality, but cannot even be thought through consistently to its ultimate logical consequences. The mathematical economist, blinded by the prepossession that economics must be constructed according to the pattern of Newtonian mechanics and is open to treatment by mathematical methods, misconstrues entirely the subject matter of his investigations. He no longer deals with human action but with a soulless mechanism mysteriously actuated by forces not open to further analysis. In the imaginary construction of the evenly rotating economy there is, of course, no room for the entrepreneurial function. Thus the mathematical economist eliminates the entrepreneur from his thought. He has no need for this mover and shaker whose never ceasing intervention prevents the imaginary system from reaching the state of perfect equilibrium and static conditions. He hates the entrepreneur as a disturbing element. The prices of the factors of production, as the mathematical economist sees it, are determined by the intersection of two curves, not by human action. Moreover, in drawing his cherished curves of cost and price, the mathematical economist fails to see that the reduction of costs and prices to homogeneous magnitudes implies the use of a common medium of exchange. Thus he creates the illusion that calculation of costs and prices could be resorted to even in the absence of a common denominator of the exchange ratios of the factors of production. The result is that from the writings of the mathematical economists the imaginary construction of a socialist commonwealth emerges as a realizable system of cooperation under the division of labour, as a full-fledged alternative to the economic system based on private control of the means of production. The director of the socialist community will be in a position to allocate the various factors of production in a rational way, i.e., on the ground of calculation.”

Naish’s use of the term ‘constant-growth capitalism’ implies that he, like many, is confusing money with wealth – and confusing the government’s favoured measure of spending (GDP) as a measure of growth. The problem with GDP is that it is flawed as a way to measure what has actually been produced by the entire economy because it does not represent production but overall spending, and furthermore the information it provides us with may actually serve no useful purpose at all. As the Mises Institute explains: “In a private market economy the aims of economic activity are highly diverse and represent individual and subjective valuations. For an economy that is to serve multiple private needs, the calculation of economic growth makes little sense, if any at all.”

Money is not wealth, it’s just a commodity that is used as a medium of exchange in order to move wealth around. So although there may be, in certain specific moments a fixed amount of money available to trade with other people for things you want, there is not a fixed amount of wealth in the world. Everyone can make more wealth and there is no limit to the amount of wealth that can be created.

Here’s a simple explanation of how wealth is created by successful investor and entrepreneur Paul Graham:

“Suppose you own a beat-up old car. Instead of sitting on your butt next summer, you could spend the time restoring your car to pristine condition. In doing so you create wealth. The world is – and you specifically are – one pristine old car the richer. And not just in some metaphorical way. If you sell your car, you’ll get more money for it. In restoring your old car you have made yourself richer. You haven’t made anyone else poorer. So there is obviously not a fixed pie.”

Naish, in advancing a theory to be implemented through government action, cannot avoid falling into the trap of all reformers, who in searching for the maximum of general satisfaction tell us merely what state of other people’s affairs would best suit themselves. Naish asserts that capitalism will lead to ecological catastrophe unless it is restrained, retarded and restricted by governments via the implementation of a new economic system. If by ‘economic system’ Naish means planned economy, then this will only achieve the opposite of its intended goal. Mises again:

“The paradox of “planning” is that it cannot plan, because of the absence of economic calculation. What is called a planned economy is no economy at all. It is just a system of groping about in the dark. There is no question of a rational choice of means for the best possible attainment of the ultimate ends sought. What is called conscious planning is precisely the elimination of conscious purposive action.

“The advocates of a planned economy have never conceived that the task is to provide for future wants which may differ from today’s wants and to employ the various available factors of production in the most expedient way for the best possible satisfaction of these uncertain future wants. They have not conceived that the problem is to allocate scarce factors of production to the various branches of production in such a way that no wants considered more urgent should remain unsatisfied because the factors of production required for their satisfaction were employed, i.e., wasted, for the satisfaction of wants considered less urgent. This economic problem must not be confused with the technological problem. Technological knowledge can merely tell us what could be achieved under the present state of our scientific insight. It does not answer the questions as to what should be produced and in what quantities, and which of the multitude of technological processes available should be chosen. Deluded by their failure to grasp this essential matter, the advocates of a planned society believe that the production tsar will never err in his decisions.”

A planned economy, however different in detail from the current one, will inevitably lead to more misallocation of resources, more waste, more over-consumption and ultimately a more severe impact on the environment. Naish’s worse nightmare. His conviction that ecological catastrophe is certain unless the vast majority of human beings on Earth adopt a certain lifestyle and change their economic behaviour fails to take into account that problems that exist now will almost certainly be solved in ways we cannot possibly imagine in the future; he is essentially projecting current technological solutions into a future where the resources we are using now are still required but in much larger quantities. This ignores the fact that the future, in terms of technological solutions, has always been exactly that which we couldn’t possibly conceive. As philosopher Stefan Molyneux has asked: could plantation owners in America have possibly conceived that in 150 years’ time giant machines that run on crushed dinosaur juice would drive up and down and pick all the cotton in their fields? Hell no. The Internet is another good example. No one predicted it would become what it is today and that it would have such a profound affect on our social and economic lives. So it’s quite rational to believe that problems that exist now will be solved in ways we can’t imagine in the future, and some of them by technologies that are in their infancy now. One such technology is nanotechnology, which, broadly speaking, is the science of manipulating matter at the atomic or molecular level. It’s the creation of computers and machines on the sub-microscopic level. Once nanotechnology reaches maturity it will revolutionise industrial processes because it will eliminate industrial pollution and by-products entirely. When you build things one atom at a time every atom is put exactly where it is needed and doesn’t end up somewhere where it isn’t. This results in perfectly built machines, in the sense of them having no mechanical imperfections, which vastly increases their efficiency and reduces the need for energy. There are already a few applications of nanotechnology in development today which are likely to revolutionise their respective fields, such as nano-medicine, nano-crystals (solar panels) and carbon nano-tubes (utilitarian structures already in commercial use, which have the potential to become the ultimate building material).

Let’s move on to discussing a philosophical error in Naish’s thesis.

Naish declares that: “Enoughism asks us to shift from self-esteem to us-esteem. Learning to see beyond ourselves also offers a way of viewing the Earth’s bounty in a sustainable way: accepting that it’s not ours, but it belongs to the universe, and so do we. We’re not lords of the earth, we are stewards, at best. So we need to lose the illusion that we truly ‘own’ the stuff we possess and consume – that’s a legal construct rather than a cosmic freehold.”

Naish seems to be implying that there is no true sense in which we can own something and that the concept of private property has no rational basis; that the concept of property only has meaning in the context of written laws and an agency to enforce them. In other words, if there were no government, then no one could rationally claim to own anything. This is not true.

Firstly, property is an observable fact and, secondly, private property is a rational moral theory. Denying either or both by believing ownership and property to be an illusion is irrational and has profound moral consequences.

Let’s prove property is a fact. Every human consciousness has exclusive authority over the physical body it inhabits, authority meaning the power to give orders, make decisions, and enforce obedience. The body is subject to the will of the individual, and this fact can be described as self-ownership. Self-ownership is what is know as an axiom or self-evident truth. A proposition is axiomatic if in order to deny the premise explicitly we must assume it implicitly. For example, the very act of denying my own existence proves that I do exist; for only things that exist can act and affect matter in reality (in this case create sound waves using my vocal chords). Thus it is an observable fact that I own my body, that my body is the property of ‘me’ (and can never be anyone else’s) because my consciousness has exclusive control over it. Property exists. We are property.

From a moral perspective this means every individual is responsible for their own body’s actions, which is good for humanity because if this wasn’t the case then morality would be meaningless. Morality requires choice and if an individual isn’t the exclusive controller of his body’s actions, then he can’t possibly choose what it does and therefore he cannot be morally judged based upon its actions. The law of causality, the relationship between cause and effect, means each individual is responsible for and owns the effects of their actions (which can be the creation of more property) and this is the basis for private property or property ‘rights’. Simply put: we own our minds and bodies, therefore we own the products of them.

Denying individuals the full freedom to dispose of all their property as they wish has profound economic and moral consequences, and can only be achieved by coercive means. From an ethical standpoint this means those who advocate such means cannot rationally claim the moral high-ground.

Conclusion

Naish’s thesis, taken solely as a manifesto for lifestyle and behavioural change, is harmless enough and may provide those who adopt its methods and practices with some useful insights into themselves and their own motivations. However, ‘enoughism’ as a political ideology is as flawed as Keynesianism because it is founded on two false premises: that ownership and property rights have no rational basis and that capitalism will lead to ecological catastrophe.

Naish is correct that the current economic system is unsustainable, it is economically unsustainable and must result in a total collapse of the system sooner or later, but he is very much mistaken in believing that a different economic system managed by a different group of people will achieve better results.

The reality is that, whether we like it or not, capitalism is the only possible sustainable system of social organisation. As our current system reaches its mathematical and logical conclusion, which is collapse, we are presented with a window of opportunity. The genius Ludwig von Mises peered through this window several decades ago:

“Imagine a world in which everybody were free to live and work as entrepreneur or as employee where he wanted and how he chose, and ask which of these conflicts could still exist. Imagine a world in which the principle of private ownership of the means of production is fully realized, in which there are no institutions hindering the mobility of capital, labour, and commodities, in which the laws, the courts, and the administrative officers do not discriminate against any individual or group of individuals, whether native or alien. Imagine a state of affairs in which governments are devoted exclusively to the task of protecting the individual’s life, health, and property against violent and fraudulent aggression. In such a world the frontiers are drawn on the maps, but they do not hinder anybody from the pursuit of what he thinks will make him more prosperous. No individual is interested in the expansion of the size of his nation’s territory, as he cannot derive any gain from such an aggrandizement. Conquest does not pay and war becomes obsolete.”

I’m certain this is the world Naish is looking for, he just doesn’t realise it yet.

Why do you think our current system is inevitably bound to collapse? Marxists have been predicting this for over a century, but the wheels continue to turn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As I understand it, Marx believed the economic system of capitalism would basically disappear as a result of it being abandoned by society as an idea, as a result of people realising its inherent immorality and flaws – in a similar way to how societies abandoned slavery. Whereas Austrian economists, like Mises as far back as the 20s, have been predicting the collapse of the economic system manifested by mixed economies governed by States enacting interventionist policies such as credit expansion etc. Today’s global economy is made up of mixed economies of this type.

Marxists, then, predict the death of capitalism. I don’t think that capitalism will be abandoned by societies. I see no evidence for that. In fact, capitalism is spreading around the world. Austrian economics has a logically coherent theory that predicts the eventual collapse of mixed economies with central banking where the State has the power to expand credit and the money supply. Of course, the one thing it can’t predict is *when* because that depends on things all but impossible to predict, psychological things like when people will lose their trust in the money supply and in the government’s ability to pay its debts.

The collapse will come, there will be a period of social unrest, then currencies will be re-tooled and people will start creating wealth again. The big question is what economic powers and control, if any, will governments have in the post-collapse environment/system? More or less? Or none? More will be a disaster for liberty. Less will be a step in the right direction. None would be ideal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So you are saying that central banking and government-controlled currencies, interest rates, etc may collapse. Certainly the long-term growth in public debt seems to be on an unsustainable trajectory.

Collapse isn’t inevitable, however. There are more optimistic scenarios:

1. Realisation by governments and electorates that public debt is out of control, followed by a default in government bonds. This could lead to a paradigm shift where the money is written off, governments reign back their scope and sell off most public assets. It’s messy, and I suppose this is quite similar to the “collapse” you talk about.

2. The growth of bitcoin and other virtual currencies challenging central banks and rendering them obsolete. Look at how the internet has trashed all kinds of industries in the past decade. This could really happen.

3. Exponential growth in technology making it impossible for governments to continue to play a relevant role in people’s lives. Capitalism by default.

4. The mixed economy, flawed as it is, continues to lift billions out of poverty and steadily solves the world’s problems. Governments continue to be part of the problem, but less so.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, absolutely, all good points. Bitcoin could definitely play a role in cushioning the fall so to speak. I agree, your number 1 is essentially what I’m referring to when I speak of collapse. It’s the degree to which our economies and our economic activity is dependent on government that’s cause for concern. If the government goes bankrupt, or at least shrinks a great deal very suddenly, then it’s likely to take a fair chunk of the economy with it – given the size of the public sector etc.. Messy is the word alright. The paper currencies, the dollar and the pound, might survive this economic reset, but I can’t see them lasting long after. They’ll have to be tied to something. Then again, by that time, people might just be happily using bitcoin anyway.

LikeLiked by 1 person